We spoke with Ali Deniz Özkan about his musical career and life story. He leads a nomadic life in Latin America after being part of several rock bands in Switzerland and the United States.

DuvaR (The Wall, national newspaper from Türkiye)

The Nomadic Musician: A Journey from Ankara to Latin America

TRABZON – Although rock music is known for its libertarian and anti-establishment nature, its current representatives often focus on market purposes. Ali Deniz Özkan lives as a nomad in Latin America and embodies the true spirit of rock music.

Özkan, the son of an Ankara family, began his musical career in Switzerland, participating in various bands and music projects. He has been composing with his one-man band, Black Sea Storm, for 22 years and gives concerts primarily in Latin American countries. Özkan pursues music out of passion rather than financial gain.

Another passion in Ali Deniz Özkan’s life is Trabzonspor, the Turkish soccer team. Despite being from Ankara and growing up in Europe, Özkan is an avid Trabzonspor fan. He named his musical project Black Sea Storm after Trabzonspor’s nickname. Even while residing abroad, Özkan never misses a game and buys season tickets. When Trabzonspor became champions, he traveled across Türkiye, giving free concerts and recitals.

Your journey has been adventurous. Can you summarize this adventure and how your musical life and travels developed?

I was born in Ankara in 1975. My family emigrated to Switzerland in 1984. I then moved to the United States in 1999 and lived there for eleven and a half years. I returned to Switzerland for six years and emigrated to Argentina in 2017. I lived in Buenos Aires until August 2018 and have since lived mainly as a nomad in Latin America.

I began my rock music career in 1991 with a band I formed with my junior high school friends. In 1994, I joined the Geneva-based music group Swoan, where I played bass until 1999. Three years later, I co-founded the bands Channing Cope and Black Sea Storm in California. I also worked as a stage musician for Kenseth Thibideau in 2010-11.

Is being an immigrant part of your reason for choosing rock music?

My earliest memory is from when I was three years old: listening to “Black Dog” by Led Zeppelin on vinyl with my father in our flat in Ankara. I’ve loved rock for as long as I can remember.

I can’t say being an immigrant directly impacted my musical choice. As a listener, I’m a natural fan of rock music. However, being an immigrant made me feel like I belonged to a cultural group. Those excluded from society can sometimes share this sentiment. My difficulty integrating during my first few years in Switzerland and feeling different revealed some sensitivities in my spiritual world.

I took piano lessons as a child, which turned out to be a fiasco. The teachers told my family I was talented but hated the classes. Learning to play children’s songs on the piano while listening to rock music at home was absurd. However, this initial defeat motivated me to make more rock music in the future.

Did your family support your musical life?

Yes, my family supported me and provided opportunities. They didn’t see much of a future in rock music until we started playing with Swoan. My father attended almost every concert we had in Geneva. I’m convinced he loved the band and didn’t just come to see his son on stage.

I’m lucky with my family. Unlike other Turkish families, they granted me a great deal of freedom and did not adhere to the restrictive cultural norms. I enjoyed greater freedom than my Swiss friends.

Regarding career orientation, my family had a typical Turkish mindset: “You have to study, you have to be successful.” But if you don’t pursue a rock music career at eighteen, when will you? It made more sense to follow my passion than to fill my brain with ideas and knowledge that wouldn’t be useful in real life.

Ultimately, I recognize that my parents formed their mentality in Türkiye, a country that is very different from the West. Ways of thinking and prejudices don’t dissolve easily, no matter how enlightened you are. It’s like trying to visit New York with a map of Paris.

As someone from Ankara who grew up in Switzerland, how did your passion for Trabzonspor develop?

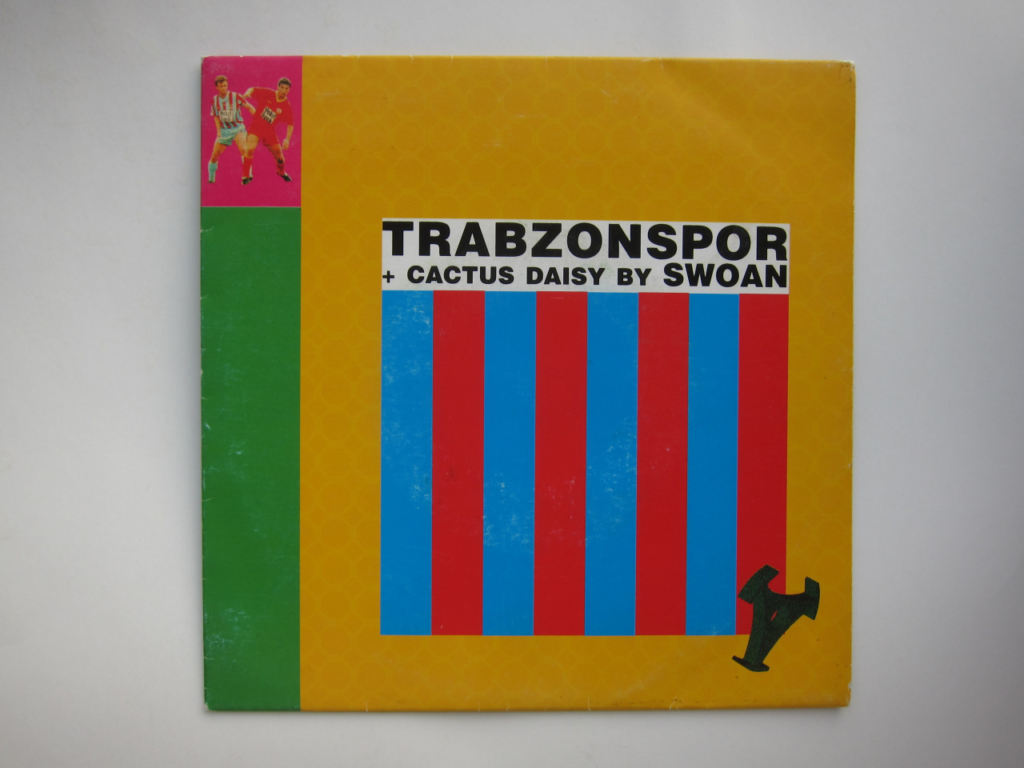

Joining Swoan and Turkish soccer matches being broadcast by satellite in Europe occurred simultaneously. From the beginning, I sympathized with Trabzonspor. We even titled one of our songs “Trabzonspor.” The band and the song started to grow, and I became a true Trabzonspor fan. We were proud of being different and unconventional, and Trabzonspor was the perfect team for people with this mentality.

Our song “Trabzonspor” became our strongest track. We received excellent feedback, especially during live shows. Everyone asked us about the song. Some knew the soccer club, while others learned about it from the song title. After a concert in Geneva, a record company called Noise Product offered us a 7-inch vinyl deal. Coincidentally, a week before the launch concert, the owners of our record label went to Istanbul and brought back Trabzonspor jerseys. We wore them at the album launch concert.

When the 7-inch vinyl was released, interest in the “Trabzonspor” song increased. My band grew with this song, turning me into the Trabzonspor fan I am today. It hurt deeply when we missed the championship in the 95-96 season, but it reaffirmed me as a true fan. After that match, I embraced Trabzonspor even more tightly.

How did the story of the band Swoan develop and end?

After my junior high school band, I played in another band called Skillings. I had trouble finding a band as a guitarist, so I started taking bass lessons. I saw an ad for Swoan, which needed a bassist, and they liked my performance.

The band’s leader, David Mamie, and I became friends quickly. We did everything together. When I joined, David composed all the songs, but he soon gave me creative freedom with the bass. We brought in Alex Müller after Vincent left the band, and the group progressed well. We released an album called “In Love” and opened for famous indie rock bands like Mogwai, and Royal Trux. However, despite everything going smoothly, the band suddenly disbanded. Swoan’s narrative reminds me of Trabzonspor’s 95-96 season, where everything fell apart just when it seemed to be going perfectly.

You always incorporated your love for Trabzonspor into your music. Do you see similarities between soccer and rock music?

Trabzonspor entered my career with the song “Trabzonspor” and remained a part of my musical work. It was a tribute to the team I love. I wore a Trabzonspor scarf on my amplifier at every gig with Channing Cope. The Trabzonspor logo was on my bass and amplifier, and I wore the jersey at some concerts.

Rock music and soccer have a lot in common. The drummer is like the goalkeeper, the bassists are like defenders, the guitarists are midfielders, and the vocalists are forwards. Like a good soccer team, a good band requires working hard together, knowing each other, and sharing the same vision. The connection between instruments in a band is as vital as the connection between players in a soccer team.

Audience engagement is also similar. Poor performance can reduce audience response, while a good performance can elevate the band’s energy. Like soccer games without spectators, concerts with tiny audiences are challenging to concentrate on.

What were your experiences in the United States and Latin America after the Swoan breakup?

When Swoan broke up, it was the biggest drama I had ever experienced, but it turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to me. I emigrated to the US in September 1999 with my bass guitar. My adventure in the US was like a movie. I started playing in a band called Bosom of the Urgent West in 2001. We founded Channing Cope in 2002, released three albums, played over two hundred concerts, and went on almost ten tours. In 2002, I also started the Black Sea Storm project.

I made a significant sacrifice for Swoan by leaving high school, a decision my family never forgave. I completed my high school education in the US within a week, followed by three years at San Diego City College before transferring to UCSD (University of California, San Diego), where I eventually graduated.

Leaving the US in 2011 was the worst decision I ever made. I returned to Switzerland, found a good job in the software industry, and worked as a manager for five years until the company was about to shut down and I lost my job. Finding a job as an executive in Switzerland was tough. Despite everything going well in Switzerland, I was unhappy and missed San Diego.

I had been preparing to emigrate to Latin America. During my time off, I went to Argentina twice to explore. I planned to move there and open a coffee shop. I earned a restaurant management certificate in Switzerland and left for Argentina permanently in January 2017.

In Argentina, I focused on the coffee project but eventually abandoned it. I found a remote job working with software companies and enrolled in a private university to obtain a residence permit, studying Gastronomy until school fees doubled. I couldn’t renew my residence permit, so I found a solution: to travel to Uruguay every three months to renew my tourist visa.

Though challenging, I began to enjoy the nomadic lifestyle. My office was located outside Buenos Aires, but I realized I could live without being in Argentina. I stored my electric guitar, bass, and heavy belongings, embracing this new life I dubbed “Endless Summer,” inspired by a song (Sonsuz Yaz) I released with Black Sea Storm. My goal was to constantly go back and forth between the northern and southern hemispheres and live year-round in the spring and summer seasons.

I adapted existing Black Sea Storm songs for acoustic guitar and started performing as a street musician, eventually booking solo gigs. I toured with my acoustic guitar for eight or nine months, then returned to Buenos Aires for two or three months to record new single albums with my electric guitar and bass.

Everything went smoothly until the beginning of 2020. I traveled from country to country, occasionally returning to Argentina to record. However, in March 2020, after recording for three months in Buenos Aires, I packed up my belongings and headed to Uruguay by boat. I planned to continue touring through Paraguay, Bolivia, and onwards to Mexico. I arrived in Montevideo from Buenos Aires in 2020, but on March 13, the borders closed due to the pandemic, trapping me in Uruguay for six months. What was supposed to be a perpetual summer in the southern hemisphere turned into an eternal winter. In September 2020, I relocated from Uruguay to Mexico and resumed my nomadic journey.

When was the last time you came to Türkiye?

In 2022, during an interview with Trabzonspor magazine, I shared my dream of being in Trabzon on the night of the championship. I planned to buy an annual pass, attend all the team’s games, and tour Türkiye with my band, Black Sea Storm, on off days.

That year, while walking along the beach in Mazatlán, Mexico, I asked myself, “Why should this dream remain just a dream?” I had absolute faith that Trabzonspor would emerge as champions. So, I decided to return to Türkiye and make my dream come true.

The outcome exceeded my expectations. The team became champions, and I was in the stands of Akyazı Stadium on that unforgettable night. We performed twenty-one concerts with Black Sea Storm across Türkiye, with our tour coinciding with the team’s victorious season. Having founded Black Sea Storm in San Diego in 2002 and performed in many countries, being in Trabzon on the championship night was deeply meaningful. Moments like these give life its true meaning.

What did you experience in the city and games during the championship process? How did you feel when Trabzonspor won the title?

The Black Sea leg of the Black Sea Storm Tour ended in Rize, one day before Ramadan. The next day, I headed to Trabzon for the home game against Beşiktaş. I planned to stay in the city until the championship was decided. The team started a series of ties, and I ended up staying in Trabzon for forty days, spending the entire month of Ramadan there. I only left for one concert in Istanbul. We finally achieved a happy ending in the match against Antalya, and I was in the stadium.

At the moment of the championship, I felt an overwhelming emotional outburst and cried. Memories of former players, coaches, and managers who had worked hard since the ’90s flashed before my eyes like a movie. This championship was not just for the current team; it was for all Trabzonspor contributors whose efforts had been overlooked and who had sacrificed so much.

My emotions didn’t lead to jumping around and celebrating. Instead, I felt a profound sense of justice being served, thinking we had defeated both our opponents and the corrupt Turkish soccer system. I left the town two days after the championship, but I will never forget those forty days in Trabzon.

You played live shows in all regions of Türkiye. In Istanbul, Izmir, Trabzon, Edirne, Konya, Eskişehir, Diyarbakir, Urfa, and many other cities. What were the places that impressed you the most?

I was impressed by the warmth of the people and the natural beauty of Hakkari Yüksekova and Şemdinli. I didn’t think Van would be such a modern city. I was surprised by the high cultural level of Diyarbakır Sur and its efforts to elevate local culture without imitating others. The location and architecture of Mardin fascinated me. I found peace and great food in Konya and Kayseri. I didn’t expect Hatay to be so socially modern.

The concerts in Artvin, Rize, and Trabzon shattered many of my preconceived notions about the Black Sea region. Trabzon, in particular, feels like home to me. The tranquility and beautiful climate of Datça were very beneficial. Edirne was very nice. I think Istanbul challenged me the most, but I found respite by visiting the islands whenever possible.

What do you think about people’s view of rock music in Türkiye?

If you open any global music platform, you will find many good rock bands from Türkiye. However, many of these groups are inactive, playing only once or twice a year. Being in a band means staying active all the time, regardless of commercial success.

The main issue with rock music in Türkiye is that it is often only accessible to individuals from bourgeois or elite backgrounds. Unlike in Europe or North America, where rock scenes can include people from various working-class backgrounds, Türkiye lacks this diversity in rock music. Imported musical instruments are significantly more expensive in Türkiye, creating a substantial disadvantage.

Despite these hurdles, the country’s lack of competition can be an advantage for those pursuing rock music. The most important factor for improving Turkish rock music is for the public to become more aware and supportive of local, original music.

What is your goal in music? Are you planning to lead a nomadic life in other countries?

My current goal is to develop my Black Sea Storm project and be a good Trabzonspor fan. If the opportunity arises, I would love to play bass in a good band again. The Black Sea Storm project goes beyond music—it involves endless travel, content production, tour organization, writing, and promotion. Doing all this requires staying healthy and strong, constantly adapting to different climates, and often being alone in distant places. I have lived in relatively dangerous locations for six years with just my luggage and backpack, and this lifestyle is not as easy as it might seem.

I aspire to take this project to higher levels while remaining independent. Black Sea Storm is a way of life for me, a stance against the exploitative nature of the music industry. Although I’m open to living a nomadic life anywhere, my financial situation currently limits me to relatively inexpensive countries where I can speak the language. I don’t see myself as a tourist; I rarely go out with other foreigners, preferring to interact with locals to truly understand their lives.

You are currently in Latin America. What is your life like there?

Before returning to Türkiye for the tour, I was in Mexico. Returning to Mexico after a year felt like a cure. 2022, which I spent mainly in Türkiye, was one of my most beautiful and colorful years. Despite the enjoyment and wonderful experiences, I was tired from my stay in Türkiye. Excessive smoking in public places, patriarchal culture, different gender dynamics compared to the West, lack of a professional approach, and generally unhappy people were draining.

I’ve found that traveling and returning to the same places gives me perspective and helps me understand myself better. Since returning to Mexico, I’ve had a concert in Sinaloa and started recording videos of live performances in various natural and urban locations. My goal is to introduce the phenomenon of travel through my music without becoming a typical YouTuber. I’ve also started recording and sharing lecture videos on rock music, sharing my knowledge and thoughts.

You have a fascinating story. Do you have any final thoughts to share?

Sometimes, it is necessary to let things go and go with the flow. I realize this more and more each day. Music is essential, and I don’t intend to give it up. I’ll continue until I can no longer play. Thanks for giving me the opportunity to share my story.